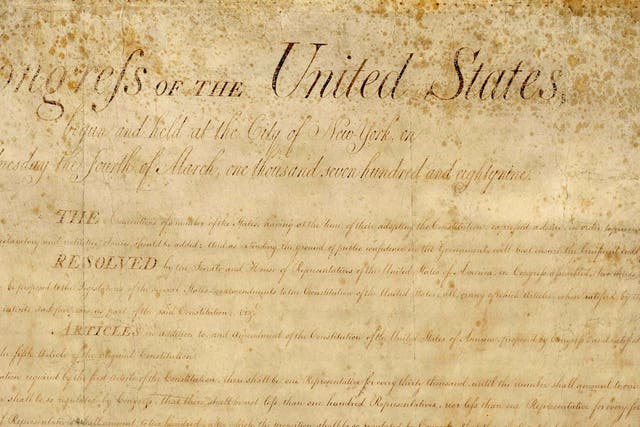

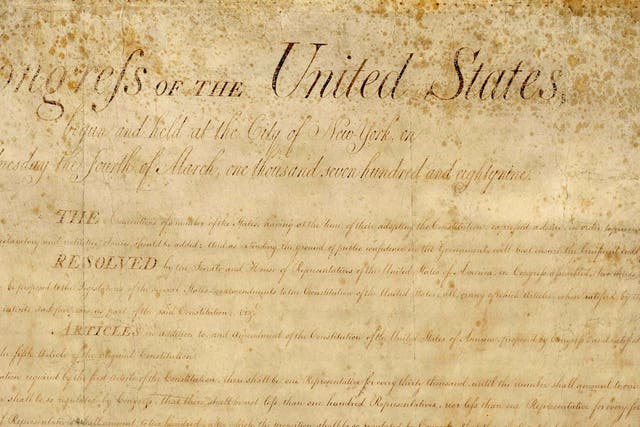

After the Declaration of Independence in 1776, the Founding Fathers turned to the composition of the states’ and then the federal Constitution. Although a Bill of Rights to protect the citizens was not initially deemed important, the Constitution’s supporters realized it was crucial to achieving ratification. Thanks largely to the efforts of James Madison, the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution—were ratified on December 15, 1791.

The roots of the Bill of Rights lie deep in Anglo-American history. In 1215 England’s King John, under pressure from rebellious barons, put his seal to Magna Carta, which protected subjects against royal abuses of power. Among Magna Carta’s more important provisions are its requirement that proceedings and prosecutions be according to “the law of the land”–the forerunner of “due process of law”–and a ban on the sale, denial, or delay of justice.

In response to arbitrary actions of Charles I, Parliament in 1628 adopted the Petition of Right, condemning unlawful imprisonments and also providing that there should be no tax “without common consent of parliament.” In 1689, capping the Glorious Revolution (which placed William and Mary on the throne), Parliament adopted the Bill of Rights. Not only does its name anticipate the American document of a century later, the English Bill of Rights anticipates some of the American bill’s specific provisions—for example, the Eighth Amendment’s ban on excessive bail and fines and on cruel and unusual punishment.

History Shorts: Who Wrote the U.S. Constitution?The idea of written documents protecting individual liberties took early root in England’s American colonies. Colonial charters (such as the 1606 Charter for Virginia) declared that those who migrated to the New World should enjoy the same “privileges, franchises, and immunities” as if they lived in England. In the years leading up to the break with the mother country (especially after the Stamp Act of 1765), Americans wrote tracts and adopted resolutions resting their claim of rights on Magna Carta, on the colonial charters, and on the teachings of natural law.

Once independence had been declared in 1776, the American states turned immediately to the writing of state constitutions and state bills of rights. In Williamsburg, George Mason was the principal architect of Virginia's Declaration of Rights. That document, which wove Lockean notions of natural rights with concrete protections against specific abuses, was the model for bills of rights in other states and, ultimately, for the federal Bill of Rights. (Mason’s declaration was also influential in the framing, in 1789, of France’s Declaration of Rights of Man and the Citizen).

In 1787, at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Mason remarked that he “wished the plan had been prefaced by a Bill of Rights.” Elbridge Gerry moved for the appointment of a committee to prepare such a bill, but the delegates, without debate, defeated the motion. They did not oppose the principle of a bill of rights; they simply thought it unnecessary, in light of the theory that the new federal government would be one of enumerated powers only. Some of the Framers were also skeptical of the utility of what James Madison called “parchment barriers” against majorities; they looked, for protection, to structural arrangements such as separation of powers and checks and balances.

Opponents of ratification quickly seized upon the absence of a bill of rights and Federalists, especially Madison, soon realized that they must offer to add amendments to the Constitution after its ratification. Only by making such a pledge were the Constitution’s supporters able to achieve ratification in such closely divided states as New York and Virginia.

In the First Congress, Madison undertook to fulfill his promise. Carefully sifting amendments from proposals made in the state ratifying conventions, Madison steered his project through the shoals of indifference on the part of some members (who thought the House had more important work to do) and outright hostility on the part of others (Antifederalists who hoped for a second convention to hobble the powers of the federal government). In September 1789 the House and Senate accepted a conference report laying out the language of proposed amendments to the Constitution.

Within six months of the time the amendments–the Bill of Rights–had been submitted to the states, nine had ratified them. Two more states were needed; Virginia’s ratification, on December 15, 1791, made the Bill of Rights part of the Constitution. (Ten amendments were ratified; two others, dealing with the number of representatives and with the compensation of senators and representatives, were not.)

On their face, it is obvious that the amendments apply to actions by the federal government, not to actions by the states. In 1833, in Barron v. Baltimore, Chief Justice John Marshall confirmed that understanding. Barron had sued the city for damage to a wharf, resting his claim on the Fifth Amendment’s requirement that private property not be taken for public use “without just compensation.” Marshall ruled that the Fifth Amendment was intended “solely as a limitation on the exercise of power by the government of the United States, and is not applicable to the legislation of the states.”

The Civil War and Reconstruction brought, in their wake, the Fourteenth Amendment, which declares, among other things, that no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” In those few words lay the seed of a revolution in American constitutional law. That revolution began to take form in 1947, in Justice Hugo Black’s dissent in Adamson v. California. Reviewing the history of the Fourteenth Amendment’s adoption, Black concluded that history “conclusively demonstrates” that the amendment was meant to ensure that “no state could deprive its citizens of the privileges and protections of the Bill of Rights.”

Justice Black’s “wholesale incorporation” theory has never been adopted by the Supreme Court. During the heyday of the Warren Court, in the 1960s, however, the justices embarked on a process of “selective incorporation.” In each case, the Court asked whether a specific provision of the Bill of Rights was essential to “fundamental fairness”; if it was, then it must apply to the states as it does to the federal government.

Through this process, nearly all the important provisions of the Bill of Rights now apply to the states. A partial list would include the First Amendment’s rights of speech, press, and religion; the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures; the Fifth Amendment’s privilege against self-incrimination; and the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel, to a speedy and public trial, and to trial by jury.

The original Constitution has been amended a number of times—for example, to provide for direct election of senators and to give the vote to eighteen-year-olds. The Bill of Rights, however, has never been amended. There is, of course, sharp debate over Supreme Court interpretation of specific provisions, especially where social interests (such as the control of traffic in drugs) seem to come into tension with provisions of the Bill of Rights (such as the Fourth Amendment). Such debate notwithstanding, there is no doubt that the Bill of Rights, as symbol and substance, lies at the heart of American conceptions of individual liberty, limited government and the rule of law.

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.

Amendment VII

In suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury shall be otherwise reexamined in any court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.