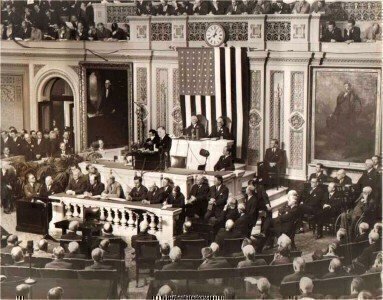

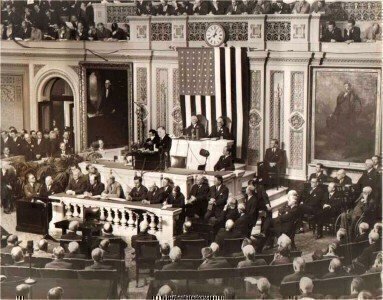

Today marks an important anniversary in American history: the congressional declaration of war on Japan on December 8, 1941. But since then, Congress has rarely used its constitutional power formally issue a war declaration.

Congress approved a resolution declaring war with Japan on that fateful day, and the Senate unanimously voted for the resolution, 82-0. The House passed the resolution by a 388 to 1 vote, with Jeannette Rankin, a pacifist, opposing the move.

“Whereas the Imperial Government of Japan has committed unprovoked acts of war against the Government and the people of the United States of America: Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the state of war between the United States and the Imperial Government of Japan which has thus been thrust upon the United States is hereby formally declared; and the President is hereby authorized and directed to employ the entire naval and military forces of the United States and the resources of the Government to carry on war against the Imperial Government of Japan; and, to bring the conflict to a successful termination, all the resources of the country are hereby pledged by the Congress of the United States,” the resolution read.

Japan had tried to issue its own war declaration just before the Pearl Harbor attack, but it failed to do it before the attack in Hawaii.

Since then, the United States has only issued five other war declarations: against Germany and Italy (on December 11, 1941) and against Bulgaria, Hungary and Rumania (on June 4, 1942). War declarations have been made by Congress in the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, World War I and World War II.

The United States military involvement in Korea came as part of a United Nations effort, while the escalation of the Vietnam War followed a joint resolution passed by Congress as requested by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964.

Since Vietnam, United States military actions have taken place as part of the United Nations’ actions, in the context of joint congressional resolutions, or within the confines of the War Powers Resolution (also known as the War Powers Act) that was passed in 1973, over the objections (and veto) of President Richard Nixon.

It also seems unlikely that an official state of war could be declared in the near future, due to the legal differences between a “state of war” and an “authorization to use military force.”

As the Congressional Research Service explains, a formal war declaration triggers a large number of domestic statutes, like the ones that took place during World War II.

“A declaration of war automatically brings into effect a number of statutes that confer special powers on the President and the Executive Branch, especially about measures that have domestic effect,” it says.

These include granting the President the direct power take over businesses and transportation systems as part of the war effort; the ability to detain foreign nationals; the power to conduct spying without any warrants domestically; and the power to use natural resources on public lands.

“An authorization for the use of force does not automatically trigger any of these standby statutory authorities. Some of them can come into effect if a state of war in fact comes into being after an authorization for the use of force is enacted; and the great majority of them, including many of the most sweeping ones, can be activated if the President chooses to issue a proclamation of a national emergency,” says the CRS.

“But an authorization for the use of force, in itself and in contrast to a declaration of war, does not trigger any of these standby authorities.”